There is the one cloud I saw in the sky yesterday. There may have been others, but not very many. It was a beautiful day on the Elizabeth River.

The wind was better than I had expected, about 8 or 10 knots or so right down the river. Lots of snowbirds passing through on their way south, like this nice ketch below. I sailed for a couple of hours, tied up in Freemason Harbor to get a sandwich and NY Times. Anchored in Crawford Bay for lunch, read the paper and then nodded off. I was just going to "rest my eyes" (as my Dad used to say) for a few minutes, but two hours later I woke up after a deep sleep.

I was also on the river the day before that, this time at a place called Money Point in an industrial area a few miles south of my normal sailing area. A few years ago this area was just shallow toxic mud, the leftovers of a creosote plant. The plant is long gone, the chemicals remain.

Government agencies, industry and local groups got together and built a rip rap barrier on the edge of the river, covered the toxic mud with clean material (they said you can't dig up that sort of river bottom, that just spreads the mess downriver), and planted marsh grass (Spartina alterniflora).

I visited some friends there while they were checking on the marine life in the rebuilt wetland. And this is where they got to measure the eel. Measuring an eel, it turns out, is easy. It's getting a hold of it that can be tough. But with enough hands they finally got it under control.

It was cool to see the vibrant green marsh grass and all the marine life that surrounds it.

They set up fish nets on a few of the drains where the outgoing tide flowed from the marsh, catching fish, crabs and eels - whatever had swam up into the marsh at high tide. They were comparing the number, variety and size of the marine left to earlier counts. I can't even remember how many different species of fish they found - spot, speckled trout, a couple of types of shad, crappie (a freshwater fish), flounder, and mullet were just some of the fish in there. In the mesh below you'll see a flounder, at left, a bunch of spot and a few other species.

They set up fish nets on a few of the drains where the outgoing tide flowed from the marsh, catching fish, crabs and eels - whatever had swam up into the marsh at high tide. They were comparing the number, variety and size of the marine left to earlier counts. I can't even remember how many different species of fish they found - spot, speckled trout, a couple of types of shad, crappie (a freshwater fish), flounder, and mullet were just some of the fish in there. In the mesh below you'll see a flounder, at left, a bunch of spot and a few other species.As for the eel, it was an American Eel, the kind that spends much of its life in wetlands but at maturity swims downriver (in this case down the Elizabeth River to the James River and then Chesapeake Bay), eventually reaching the Sargasso Sea hundreds of miles away where it will spawn. It was an interesting connection between this beautiful rebuilt wetland miles upriver on a very industrial waterway and the deep blue Atlantic Ocean.

The eel, once under control and measured at 22 inches, was released to swim back into the Elizabeth River - a river that is, at least in places, on the mend.

steve

4 comments:

My Grandmother always used to say, "Eels are fine for eating. They move around alot. It's the fish that stay in one place all day that you have to worry about. Eels could be at the head of the Metedeconk in the morning, and be at the Manasquan Inlet by the end of the day!"

The proper way to skin an eel is to nail the head to a tree in the yard. Take a sharp knife and slit the skin all the way around the neck. Then with pliers, grab the skin and pull it all the way down off of the eel. Then, cut into two inch sections, season well and dredge in flour and pan-fry 'til golden brown. The meat is pure white and is sweet tasting. Can also be pickled for a winter treat.

Hi Steve

I talked about you again in my blog. Look the beginning of my post. If you don't like some of my words, tell me and I will change them.

Good winds

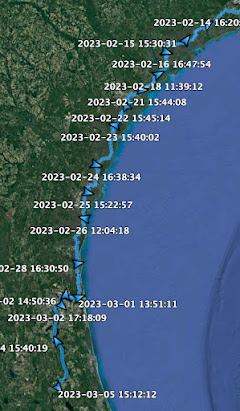

Fernando "Estrela d'Alva" Costa, from Cabo Frio, Brazil.

Bom dia colegas velejadores

Acabo de ler o diário de bordo dos primeiros 4 dias, da última expedição do Steve do "Spartina", em Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, EEUU. Muito interessante. Copiei meus extratos prediletos em inglês e os comentei livremente em brasileiro pra vocês. Espero que gostem. Steve, amigos, é o único velejador do planeta Terra, que eu conheço, que gosta de fazer o mesmo que eu. Pequenas expedições a bordo de um pequeno veleiro tradicional, ao longo da costa, que é o lugar mais perigoso dos oceanos.

Day One - Rumbley to South Marsh Island

1 - I tried a couple of times, struggled, then waited about 30 minutes and during a lull in the breeze dropped the mast into place.

Enfrentei o mesmo problema este mês Steve. Ventos fortíssimos quase me impediram de retirar e depois de recolocar no lugar o mastro de 7 metros e apenas dez quilos da “Estrela d’Alva”. Isto com a ajuda do meu amigo “Aguavel”. Ligado?

2 - I don't like to make any big changes on the boat without a lot of thought.

Ótima idéia Steve. Como meu veleiro é menor que o seu e minhas expedições mais longas, eu nem costumo velejar durante os primeiros dias de expedição e costumo citar meu paradoxo: “ O marujo só deveria partir pra MAR, após uma...

continuation here:

http://estreladalvacabofrio.blogspot.com/

Thanks for the post Fernando. Yes, 6.6 knots and yes, I understand your concern about the outboard.

Fair winds.

steve

Hi Steve

I made some mistakes writing my last post about your expediton. Now I think it's better. Look!

Good winds!

Fernando, from South Atlantic

2 - I don't like to make any big changes on the boat without a lot of thought.

Tem toda razão brother Steve, antes de fazer qualquer mudança, pequena ou grande, a bordo de um barco à vela, convém pensar muito. Muito mesmo. - Porque? Perguntaria o leitor que nunca velejou. - Porque por trás da aparente simplicidade do barco à vela, mora uma grande complexidade, leigo leitor. Portanto, qualquer mudança mal planejada, pode trazer trágicas conseqüências. Assino em baixo da máxima do Steve.

Post a Comment